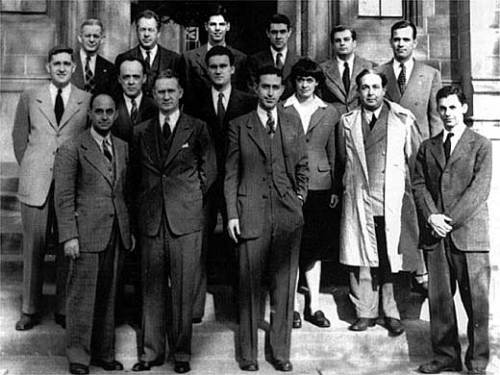

Chicago reactor team. Enrico Fermi, first row, first on left.

For more than a year, physicist Enrico Fermi and his team had been building a pile of blocks under the racquet courts at the University of Chicago.

The pile was made of alternating bricks of uranium and graphite.

Inserted into the pile were cadmium coated rods that could be withdrawn.

This was the world’s first nuclear reactor and no one knew if it would work.

On December 2, 1942, Fermi and his team began to withdraw the cadmium rods.

Cadmium has the power to absorb neutrons. The uranium, being radioactive, gave off neutrons. And each time a neutron from the deteriorating uranium hit another uranim atom, it caused a small reaction which gave off both heat and an addition three neutrons. As neutron hit atom and each atom in turn went from U238 and U235, the newly formed atom of U235 in turn gave off an additional 3 neutrons. One became 3 became 9. 3 to the third over and over and over, each giving off more and more energy and the reaction took off. The pile went critical and the reaction was self sustaining for 28 minutes.

The world’s first chain reaction.

The successful experiment under the University of Chicago’s football stadium was the foundation of the Manhattan Project and the basis of the Atomic Bombs that the US would ultimately drop on both Hiroshima and Nagasaki three years later.

New technologies do not occur in a vacuum.

Once unleashed, they, like the pinging loose neutrons in Fermi’s pile, begin to set off a series of chain reactions impacting on other technologies and industries until those industries and technologies are also changed… or simply explode.

Take the Internet.

The Internet itself was the product of the US military’s desire to protect command and control from the power of nuclear weapons. As warheads grew ever larger in megatonnage, the military had initially responded by burying their command deeper and deeper in the earth.

It soon grew apparent that it was far easier to ratchet up the megatonage of the bombs than keep digging deeper into the earth.

So the military went to the Rand Corporation and asked them for a solution. They came up with a rather novel one: networks.

If you build a network of nodes, they said, connecting the nodes together, then even if one or two or four nodes are destroyed, the others will continue to function.

The US Dept of Defense did just that. Under their Advanced Research Projects Agency, ARPA, they built something called ARPAnet. A network of mainframe computers joined together by phone lines. Think The Forbin Project.

This ARPAnet was to become the Internet. Opened to the public, it’s network growing far beyond its initial 8 nodes to what we know today.

As each new node was added, as each new computer and user and server came online, as each new functionality was added, the national network of the web, formerly Arpanet, now grew, a bit like Fermi’s pile in Chicago. Each begetting more and more and each new line of code or added function or added computer adding more and more, larger and larger, until it hit critical masss itself.

Had you told the people building Arpanet for the Defense Department that their 8 mainframes and dial up telephone links would one day destroy the newspaper business, they would have thought you insane.

But it did.

Had you told them that it would destroy all the television networks in the country, they would have had you institutionalized as a raving lunatic.

But it will.

Had you told them that it would one day render Bell Telephone worthless because you could use VOIP protocols for free, they would not have had the vaguest idea what you were talking about.

But all of that was to come true.

It was the inevitable result of the chain reaction set off the day Bolt Beranek and Newman, the engineering firm hired to build Arpanet, turned it on.

As Andy Grove, the Chairman of Intel said, “listen to the technology. It will tell you where to go”.

Look at the confluence of technologies impacting now on the television and journalism business. Cellphone with video cameras inside. A web that carries video content globally for free. Listen to the technology. Where is it taking us? It may not be where you want to go, but most assuredly, this is where we are headed.

And unlike Fermi’s reactor in Chicago, there is no way to turn it off or to slow down the reaction. We are rapidly approaching critical mass.